|

Subtitle: What we gotta do to get you Natives to stop complaining? Sub-Sub Title: You could start by moving the whole "Natives in Movies" thing forward and actually tell some better stories. Truth be told I'm often too busy to read the news. So I end up getting most of my news from my constantly updating Facebook feed (apparently, I am not too busy to visit Facebook). This is how I came across the following story: Johnny Depp and Armie Hammer as Lone Ranger and Tonto -- FIRST LOOK! My immediate reaction was "no Johnny, just no." Johnny Depp and some other guy (and does it really matter who the other guy is? It's a Depp vehicle. Look at how that guy who played Barbosa or even the monkey often stole the Pirates of the Carribbean film from him, but we don't remember their names) are making a new Lone Ranger and Tonto movie with Depp starring as, you guessed, Tonto. (or maybe you didn't guess it. Maybe you thought he would play the "main character" of the Lone Ranger and a Native actor would be playing Tonto, well - Surprise!) But don't worry, Johnny is Native too. I say that with very little sarcasm. Maybe as Depp says he is a Native person of the "Cherokee or maybe Creek origin" or whatever. Maybe his great grandmother was an Indian princess who married his great grandfather after she was relocated due to a boarding school program that thought she would be better off living in the city so she could erase her culture through assimilation. Maybe the historical trauma experienced by his native great grandmother caused an irreparable fracture whereby she disappeared into the masses of our society and did not want to clarify for Johnny exactly what tribe she was from. Or maybe it's not my job to judge Depp's Native identity (it would, however, explain why he is so darn good looking). The real question is, Indian ancestry or not, could the remake of The Lone Ranger and Tonto ever really work as a good idea? (And I'm not just talking about an "entertaining" or even "bankable/ marketable" idea. I'm saying, could it ever work in a way that doesn't contribute to the continued exploitation of Native people at the hands of an outdated, outrageous stereotype?) The short answer - no. An even better answer - why try? There are so many other better movies that could be made or marketed. Recently I heard about a movie where Natives on the Rez were fighting zombies, and it's funny too. What about any number of books that have been written about Native peple that have yet to make their way to screen? Call me Johnny - we can talk. (I have this script we can look over... because who doesn't?) The long answer... no. No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. You see, The Lone Ranger and Tonto started in 1933 when a hero of the expanding West (The Lone Ranger) and his trusty sidekick (his horse!) and then the other side-side kick guy (that would be Tonto) would set out via the radio each night to help solve some problem that needed solving. And of course push forward this whole manifest destiny thing and help "tame" the wild frontier to get it ready for western expansion. Yes, that's what it was really about. Chadwick Allen writes in "The Hero with Two Faces: The Lone Ranger as Treaty Discourse" that the Lone Ranger and Tonto was ultimately about the conquest of the Western frontier. (And I agree with him - so that makes it ALL OKAY!) And for Allen this meant that Tonto was "...the idealized Indian" who "operates as an 'island of Tribalism' in a frontier imagined as overwhelmingly white, supervised and supported by the 'governmental' authority of the idealized white ranger" (612). Yep, that's what it was really about. Tonto was a good Indian. He was an Indian that continuously helped the western expansion by solving problems on the Frontier that would eventually lead to the killing, displacement, and destruction of Native people. The radio show went international in 1934. And by 1955 it was broadcast by "249 US stations and had the highest rating of any radio western, reaching an estimated 12 million listeners each week" (Allen, 613). It then also became a television show, movies and all around merchandising powerhouse. So what of this movie? I haven't seen it. But I have pause and trepidation. First, Disney is the major studio attached to the making of this project. The writers for the movie are all non-Native people who are closely tied with the movies Pirates of the Carribean and Aladdin (known for it's sterotypical portrayal of "barbaric" Middle Eastern people and it's portrayal of a 16 year old girl who HAS to marry a Prince or otherwise be disowned by her father).  _Disney's involvement is particularly concerning being that Disney is a company that does not exactly have a good history with their treatment of Native peoples. The portrayal of the "Red Man" Indians in Peter Pan alone should inspire some trepidation. Of course, there is also the cartoon wonder that was Pochahontas. Native men in that movie were portrayed as boring, boorish and backward and poor Pochahontas herself was portrayed as America's princess all too eager to help the colonization project along. And let us not forget Disneyland - which at one time included an Indian village. The Indian Village sighting was originally a part of the "Jungle Cruise." And around the "Frontier Land" area you could stop by a store and buy all your cowboys and Indians gear, and then go to the fort to shoot at some Indians. (I haven't been to Disneyland in a while, but the last time I was there you could still buy yourself some good old Indian florescent pink and yellow feather war bonnets and a tomahawk, because with those bright feathers nobody will ever see you comin'! ) But even more, the studio and actors seem to know there will probably be an issue. They've already stuck Depp out there in front of the news media to address this issue. Almost as if having their "real Indian" get out to talk about how great this movie is actually going to be for Indians should somehow make everyone stop fidgeting uncomfortably around while they release pictures of Jack Sparrow with a bird on his head. Depp himself is paraded around to assure us that "I like the character. I think I have interesting plans for the character, and I think the film itself could be entertaining and very funny. But I also like the idea of having the opportunity to make fun of the idea of the Indian as a sidekick - which has always been [the case] throughout the history of Hollywood, the Native American has always been a second-class, third-class, fourth-class citizen, and I don't see Tonto that way at all. So it's an opportunity for me to salute Native Americans." And let me make special note that just because Johnny is Native and agrees to making the movie does not mean that this makes it a good idea. It doesn't mean there aren't any problems any more. This has happened to me a lot. "I see you wrote that this play is totally problematic in its portrayal of Native people, but guess what we met this one Native guy who said it was fine so that makes it ALL OKAY!" The "feeling" that there is something up with this whole "Tonto" thing, that's real (Disney and the people making this film). You should listen to that instinct. You should try to do something about it aside from trying to get us to back down because Johnny Native came out and said it was ALL OKAY. Find out about this history, Disney. Find out about what it means to be a "Tonto", watch Reel Injun, read books about the portrayal of Indian people in films, have a talk with some other Indians (because we know you have your one guy, but you can have more than one talking at you... it's alright). Diane Krumrey writes in her essay "Subverting the Tonto Stereotype in Popular Fiction, or, why Indians say 'UGH'" that "...the winning combination in a frontier novel had to include an Indian, male or female, who loved and supported the main character away from danger, who would even sacrifice him - or herself to preserve the whites. In America, this has come to be known as the Lone Ranger and Tonto Syndrome..." You see Johnny, it's a syndrome. It's a real thing. And it's still carried with Native peoples, especially those who have to go to the movies to watch as we become tall blue animal like creatures who have sex with our hair, or shirtless extra warm werewolves, or primitive monkey like people who try to protect our greatest secret, that aliens were made of crystals and gave us all of our knowledge. Tonto is a thing. Being called a Tonto is a thing. Maybe you can try to re appropriate Tonto, maybe it's a bit of an admirable goal, but did you see what they did with Pirates of the Caribbean III? If you couldn't control that monster - how in the hell are you going to control this? And in the end, we watch as once again a Native person is portrayed on screen aside a strong, valiant white character. We wait and wonder what happens next. We listen as people wonder "why was that such a big deal anyway. Tonto was (insert nice adjective here, funny, smart, strong, deeply in touch with the earth, better at shooting a bow and arrow)" and then we go home and think about how we don't really ever get to see portrayals of Native people on screen that don't somehow involve old stereotypes that refuse to die. And then my daughter goes to school. And I remember being in school and being the Indian girl there. Granted, I never took the time to ask these kids if their motivation for what they portrayed as "Cowboys and Indians" was mostly influenced by their own imagination or if it was as a result of what happens in the movies. But I have a feeling. Because you see, Johnny, what happens with these movies might not seem real to you, but it's real. When I was in elementary school I had long, dark hair that I wore in braids. Little kids would dance around me sometimes and whoop and holler. They would pull my braids and call me "Pochahontas" or sometimes "Wild Flower" or "Indian Girl." "Where's your bow and arrow Pochahontas? Why don't you growl around like a dog? How come you aren't dancing around and whooping like this?" (Boy starts dancing around like and Indian around the fire making whooping noises). And one time I watched as they played Cowboys and Indians, which for them meant grabbing some kid and pretending to tie him to a wooden pole where they set him on fire while dancing around him (those were the Indians). In rode the most powerful cowboy. He had the power to put out fire and rescue this kid. He also had the power to kill every single Indian in sight. At the end of it all as he was riding away he stopped in front of me and spit at the ground. "Don't mess with us you Indians" he said. End scene. Look Johnny if you want to contact me click on the contact button above. I'm happy to talk. My mom has the biggest crush on you by the way. It's part of the reason why I can't say that I do, because that would be weird to have a crush on your future stepfather.

1 Comment

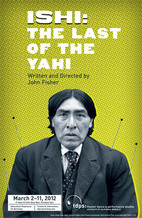

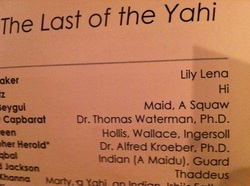

You know when I was little I used to say "well, I gotta go be an Indian today." For me this referred to when I would dress up and go to dance in a pow wow. When I would see Native people dressed up to go to a pow wow I'd say "look Mom they are going to be Indians today." I didn't consider it "being an Indian' when I went to my tribal ceremonies, however, I just thought that's what we did. For me, being an "Indian" was the whole powwow thing. That thing you see on TV. That thing that's been in the movies. I also once asked my mother why we didn't go to church. And she said something about how whenever we went to a ceremony it was kind of like we were going to church, if I needed to draw some sort of parallel to Western culture (can you tell I was raised by an academic? Smartest, best one ever...) And I said "no, you know, a REAL church, the kind where you stand up and sit down a lot and someone lectures you and you sometimes sing boring songs and then at the end you eat cookies" (can you tell I went to a "real" church one time and all I really remembered was eating cookies?). I never really felt like an Indian on a regular basis. I never really felt much different then the kids I went to school with or the other kids I went play basketball with (although many of those were my cousins. At least the ones who were really good at basketball. And there is something that people don't tell you a lot, Natives are really good at basketball. Epically good. Except for me...). Growing up being an Indian on a regular basis meant for me - being inconvenienced on a regular basis. Sometimes I had to miss school to attend ceremonies. Also my grandmother always told me things like acting like an "Indian" meant that I respected elders, that I was always clean, that I sat up straight, that I didn't yell at my parents, that I walked carefully on the earth (as to not step in the dirt and get my new shoes dirty). It also meant that I didn't say things like "whatever" or "dude" or "shut up", especially not to my Indian Grandma, because having an Indian Grandma means that the most powerful woman in the universe is standing in front of you so you better not try to talk to her with a smart mouth. And then there was fourth grade when we (being at a public school in California) were supposed to learn about the Missions. You know, how the Catholic Missionaries came to California and brought the poor Indian people into the missions where they fed then and gave them agriculture and told them a little about God. I was supposed to make a diorama where I put those poor Indian people gardening and those nice Missionaries standing next to them helping them to garden. When my Mom showed up to tell the teacher that I would not be building a Mission and I would also not be learning about Missions in this way, she instead offered to bring in additional information for the class. It was both Grandma and my Mom who came and did a presentation about what it was like to be Native in California, about canoes and baskets and singing and ceremony. They also had me dress up and walk around the class to show them what I looked like when I danced. And then a few months later my Mom took me to the Mission Carmel where she told me about how Native people were buried in mass graves under the mission as many of them died while helping to build it. She also told me about the enslavement of Native people, how they were beaten, tortured and disregarded. How the missions meant to destroy Native people by either killing them, or killing their culture. The tour guide lady who was listening in while we talked had this horrified look on her face. I have this responsibility now - to tell these stories to my younger cousins, me nieces and nephews, and my daughter. I consider this a great honor. I consider it a honor and an imperative. In California there are a lot of Native people. It has always been this way. Pre-contact populations have California at the highest population above Meso-America. And now, we have one of the biggest Urban Indian populations (in LA) and some of the highest population rates per capita in certain areas. We're growing. Yet, we still work have to work every single day to remind people that we are still here. One of the reasons I study Native American Studies is because I see the value in Indigenous epistemologies. The deeper we study the universe, science, health, humanities, philosophy, thought, or many other areas - the more we see how Indigenous societies had and valued a very deep knowledge that contains the answers to many of the questions we have about - of the interrelatedness of all things - of the responsibility, reciprocity and respect that is a part of existing "in a good way" on this planet. The future of "development" of "evolution" or "science" of "technology" of the very society itself really does depend on the understanding of these epistemologies. The value of this knowledge continues to grow among Western thinkers and researchers and one day all of the knowledge that was lost, ignored and destroyed may finally be used as a way to move forward. I was inspired to write this post because of my previous "Ishi" posting - about the play that was performed at UC Berkeley that was rooted in the glorification of trauma and an ignorance to the continuing existence of Indigenous peoples. You can read the entire thing here. I plan to write an update post very soon. In the course of conversations with people who emailed, called, Facebooked and approached me in person one person (who herself was wondering if there was a slippery slope between "censorship" and "you've offended me with this play") said to me "so being an Indian on a regular basis must mean you're pretty much offended about something all the time, right?" I actually wasn't offended by this question which made me feel oddly vindicated and I almost threw my hands in the air and went "HA!" I've been asked a lot crazier question in the course of my Native life. It's just what people start to think. We're always pointing out the problematic representations of Native people. We're always asking for opportunities to speak for ourselves. Part of the problem is that there is still a feeling that there are no real "Native Americans" who can actually speak to their experiences because real Native Americans died a long time ago (and there is a WHOLE lesson plan that needs to be inserted here about why people want all Native people to be gone that has to do with claim to the land and distancing oneself from the responsibility for the genocide and holocaust that took place on the same land where we live each and every day). The statement though - it made me think about this, what's it really like to "be an Indian on a regular basis." Being a Native person on a regular basis for me has been what it has always been - telling stories. By telling stories we give voice, we provide testimony to those things that other seem so quick to forget. We speak up in public places to remind people "we are still here." We provide alternative narratives and view points and ask questions, we are always asking questions. We live the past as we live the present as we live the future. We like laughing (hanging out with Native people is probably the most laughing you are ever gonna do, ever). And on those occasions where we "have to go be an Indian today' we do it, not just because it is meaningful and spiritual and beautiful - but because we are not so far away from a time where people died to be able to carry on these ways of balancing the earth. We never really "lost everything" and we are not so far away from when we were walking this earth "in a good way" - in fact we are so much closer each and every day. The picture above is of the Trinity River which is the river that runs through the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation. Picture by me. I went to see "Ishi: Last of the Yahi" at UC Berkeley and all I got was this blog entry. (Review)3/11/2012  Ishi: the Last of the Yahi is currently being performed at the Zellerbach Playhouse on the UC Berkeley campus and runs through today (March 11). I attended the play as a guest of my cousin, Kayla Carpenter, who is attending UC Berkeley as a graduate student in Linguistics. We are both Northern California Native peoples. I am enrolled in the Hoopa Valley Tribe with ties to the Karuk and Yurok peoples. I am also a PhD Student in Native American Studies at UC Davis where I focus on Native American Literature, Native American Women, California Indian History and Contemporary Society, Indigenous Politics and Contemporary Society, Indigenous Methodologies and the Decolonization of Theory. The play was originally introduced to me by another UC Berkeley Graduate Student, Tria Andrews who offered a review after she was required to attend the production for class. I recommend reading it. I offer this response to my experience attending this play as a way of continuing the conversation "in a good way." Thank You. First let me tell you about the point where I almost walked out. Ishi, having been living in the Museum of Anthropology at UC Berkeley for a few years was finally brought back to his home (Deer Creek) by Alfred Kroeber, his junior faculty Thomas Waterman and Dr. Saxton Pope (who will eventually be the person that betrays Ishi's wishes and dissects his body and harvests his brain to send to the Smithsonian). At Deer Creek a number of "hilarious" things happen, Kroeber admits that he doesn't really like nature all that much (and misses his wife), all the European American characters get together and sing cute little songs like "She'll be comin' round the mountain when she comes (yee haw)" and Dr. Saxton Pope (of the brain harvesting popes) "goes Native" where she dresses in a two piece buckskin outfit (am I to assume she bought these from a street vendor in Berkeley before she left? Or perhaps at Forever 21 or Urban Outfitters?) and simulates giving birth while whooping, hollering and standing up. She also tears the umbilical cord with her teeth, as a real Native woman would do. It's meant to be tongue in cheek, I get it. These crazy European American scholars, tee hee, ha ha. In the mean time, they want to continue to pressure Ishi to tell his story. His story will make them a lot of money, you see, and "build them a museum." When Ishi finally does tell his story it rests with the fate of his sister. You see Ishi and his sister had been in an incestuous relationship for a while now but then she was "raped" by a white man. However, when Ishi points this out to her she desperately clings to him and says "First I was unwilling, now I am willing. This makes it alright." It was at this point I started gathering up my things. I couldn't take it any more. First Ishi is just "a man" and then he is a man who has sex with his sister and then he is a man who kills his incestuous baby by drowning it in a creek because they are trying to get away from being hunted by the "colonizers" of California. And then he is a man cuckholded by his own sister who has to let her go or otherwise she may say things that he doesn't want to hear and "If she said it, I knew I would beat her, I was almost beating her now." Later Ishi helps to kill her half breed baby, because the sister believes this will mean she can be with her man. Why Ishi helps her is a little unclear. Why he sends her to her death is also a little unclear. Anyway you cut it Ishi's sister doesn't have a name, she's just called "Woman" and in the end her last line is "Good. Dead. Dead for you." I eerily felt like she was speaking to the playwright himself. There's been a fair amount of controversy over the staging of this play Ishi: The Last of the Yahi written and directed by John Fisher for the UC Berkeley Department of Theater, Dance & Performance Studies. You can read a beautiful and poignant review and initial reaction by UC Berkeley Graduate Student Tria Andrews here. Faced with watching this play for class, Tria wrote this review as an immediate response to the careless, horrific portrayal not just of Ishi but also of Native people in general in this play. It was because of that review that I attended the play along with other students and Native peoples who wanted the opportunity to "talk back" to the staff after the show was completed. As a result of the hard work of the American Indian Graduate Student Association at UC Berkeley there were two inserts added to the program, the first being a "response" quote from Director/Writer John Fisher and the second being a statement about Ishi written by the Native American students. John Fisher's statement is as follows: As I state in my "Authors Note," Ishi is a work of fiction based on fact. I have combined research with creative writing to make the point that the California Holocaust was a horrific event; its perpetrators ruthless and sadistic. There is much we do not know about Ishi's life before he came out of the woods, and I have tried here to depict how terrifying that life might have been and how egregious life during any genocide must be for the victims. For a factual account of Ishi's life and the harrowing aspects of his genocide, as well as Ishi's subsequent exploitation by men like Kroeber, I recommend most highly Orin Starn's "Ishi's Brain". The students, on the other hand provided a touching quote from Ishi himself, effectively giving Ishi the voice that he is denied throughout the play. When I am dead, cry for me a little. Think of me sometimes, but not too much. It is not good for your wife or your husband or your children to dwell too long on the dead. Think of me now and again as I was in life, at some moment which is pleasant to recall, but not for long. Leave me in peace as I shall leave you, too, in peace. While you live, let your thoughts be with the living. A poetic and beautiful statement which clearly illustrates that Ishi was an intelligent and insightful human being. Throughout this play he often speaks in broken, short, "Indian" speak such as "No, you stay. I go." (this is in fact his last line) or "One good thing, no more therapy. No more questions. I do my rounds." In fact, at the end of the play where "Ishi" finally gets to make his eloquent speech about the perils of manifest destiny and the trappings of "survival" it is not Ishi who makes this statement it is (as written in the script) the actor "dropping character, rising and speaking as the ACTOR who plays the role." Nowhere do we get Ishi's voice in this play, at no time is Ishi given the real opportunity to show that he is much more than "a blank slate waiting to be named and reinscribed" or that "So much was taken away by the time he came to us that we wasn’t a Yahi man with a Yahi name anymore, he was a no one." This is the "ACTOR" speaking as himself at this point, lecturing the audience, reminding the audience and anyone they pass this information along to that by the time these Native peoples were coming out of the woods they were utterly destroyed. They were falling apart (granted at the hands of the genocide going around them) but, you know, "manifest destiny was a two way street" and it was a degenerate time, where all people were driven to degeneracy. Especially those, as Dr. Saxton Pope states about Ishi's sister who "had no cosmology, no morality, so she created her own." The implication here being that Ishi and his sister were denied their cosmologies because their father was killed when they were so young. Left as "wild children" they raised themselves so they naturally degenerated into an incestuous relationship that resulted in violence and ultimately the death of the sister as a result of her ignorance, and the death of "Ishi" or his "true name" as after this he decides to leave the woods to "die." I am floored. Ishi was a person. I want people to consider the legacy that Ishi tried to leave. He told stories, old stories, from his tribal peoples. He wanted their "cosmologies" to be acknowledged. He was 49 years old when he "came out of the woods" and he was well aware of the society around him. His camp included pots and pans and tents. He was also, to be frank, not the last of his tribe. The fiction created by Kroeber, created by Berkeley, created here by John Fisher, is the continued exploitation of a real person who lived the last five years of his life in a museum. Fisher is not more innocent because he also portrays Kroeber as an arrogant, flawed, self centered man. He is not more innocent because he "knows" about the "genocide" of Native peoples in California and wants to use his "art" to shock people into "having a conversation." He is not more innocent because he hides behind historical fiction and calls it "based on fact." At the end of the play, having been subjected to the killing, fileting, burning, raping and molesting of Native peoples all over the stage. After having watched Native characters being "hunted" and chased around the theater, sometimes set to "cartoon" music. After having watched as Ishi drowned his child, beat and "raped" his sister, and was beaten by his own father -- I was exhausted. My stomach had a huge knot in the center. My neck was stiff. I listened to the tears falling from other Native peoples in the audience around me. I watched as my cousin clenched her hands tightly together and waited. The lights went up, people applauded, but I and several others around me did not. I waited anxiously for the "talk back" and wondered what others in the audience would say. My cousin relayed to me that one man had walked up to her at intermission and told her that he had done work with the Hupa people before and that he was leaving the play in disgust. I had watched after intermission as the audience grew smaller on both sides. I didn't prepare any questions or statements but wanted to wait to see what others had to say. After a statement by the Department at Berkeley, my cousin was given the opportunity to speak. She offered a prayer. And while I do not plan to transcribe the entire prayer I thought it was a beautiful illustration of the cosmology and ontology of Native peoples, especially those of California. This society (still alive, still vibrant FYI) had within it concepts of "growing old in a good way" and had a deep knowledge of the universe that while scarcely approached in scholarship and research holds within it answers to some of the deepest questions of Western knowledge. Ishi's language was no different. And this insistence at portraying him with "Indian" speak, or broken English only further shows the ignorance of this play. When the Writer/ Director finally spoke it was in response to a question from the audience. "Exactly how much of the story was based on fact would you say?" Fisher's response was this: In sort of framing my participation tonight I think this is a work of art and the attempt to defend it of necessity must collapse on itself. I had very clear motives in creating it four years ago. It is now in its second incarnation and to talk about specifically what is story and what is fact I think is to attempt to explain it. And I can't really speak to explaining it, to defending it. I feel unprepared to answer that question. From the audience I heard someone mutter "what?" And I felt the same way. We had stayed because of the "opening of dialogue" and "breaking ground for conversation about sensitive issues" (all statements made at the start of the talk back) and now we were told that there would be no effort to "explain" this "work of art." The talk back continued with people speaking about the effort to "create dialogue" by the play and "calling attention to these issues." After one audience member asked for a response from the American Indian students about why they didn't like the play a Native man stood up and took the microphone. He couldn't finish his statement and it ended in tears. It was a meaningful illustration of what this play really does, it doesn't open dialogue, it glorifies trauma. It erases the real, living Native peoples (some of whom are Ishi's relatives). It forgets that those people could be sitting in the audience. It refuses to dialogue with them when they ask real questions, how can you justify portraying Ishi and his story in this way? Why do you use this opportunity to give him a voice to destroy that voice? Why must you "confront" us with these images of the holocaust and genocide but also include a pseudo-justification for it by allowing that "even the Natives were participating in these atrocities - against each other?" Why would you take a peaceful, intelligent man and belittle his story to a sensationalist, animalistic portrayal? Why will you not acknowledge that your "art" could have been better? And now that you have access to Native people who want to have a dialogue with you and offer real feedback so that you can learn something and also teach others why won't you actually talk to them? But I didn't say any of those things. Caleen Sisk offered a response as the Chief of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe of California. She had traveled from Northern California to see the play for herself. Her tribe are relatives to Ishi's tribe. And after she was finished and another man spoke (who was slightly disturbed himself at the portrayal of Ishi) I took the microphone. I offer my entire statement here for you to read. I spoke without writing anything down and from the heart. I did not expect to be so personally affected by what I was seeing on stage. I did want to take the opportunity to tell everybody here and all of the people in the play that I don't want you to leave thinking that Ishi is a rapist, that he had sex with his sister, that he killed a baby- that he was a part of it. I want you to go out and find out about him. He was a gentle, peaceful person and he gave of himself personally to keep the dialogue going. And for that to be what anybody walks out of this place with- it's a tragedy, because we fight every single day to be heard and I don't want you to just hear that. And I think there is a real opportunity here for everybody involved to take a step back and understand that you can change this. And I know that it feels very personal, I myself am a writer, and if somebody were to come tell me to change something that I made it would be like changing one of my children, but this is different. You don't get to hide behind historical fiction; it doesn't work that way. Not when you have a people who are based in what Kayla was talking about- to grow old in a good way, to be whole and balanced. If you leave here tonight with one thing repeat to yourself- that was not Ishi, that he deserves more, he deserves a real voice and take it upon yourselves to figure out how you are going to find that voice for him or you will have done him a great injustice again. There will be a followup "dialogue" on Tuesday at 4pm in the Durham Studio Theatre in Berkeley. I have also heard that people have gone to sit outside the play to sing and call attention to the lies about Ishi. The last night of the performance is tonight. The images -- they will stay with me -- but I will let only the good things in and none of the bad. Ts'ehdiya.  Here is the picture I took of the program for the play. Notice the third character(s) down are listed as "Maid, A Squaw"... And then even further down you have "Indian (A Maidu)". So while the male Indian gets at least some tribal affiliation (and that's not to say even this is the best designation for these characters) - the Native Woman who is raped and killed after she first appears is simply known as "A Squaw." I write more about this in the comments below. To keep people updated as things happen I am adding on the following part to this review: Here is the article where the Theater Department at Berkeley apologizes for staging the play. Here is an article written for The Daily Cal by the Native Graduate Students about art and ethics and the play. Here is a blog entry by a Professor at Berkeley which talks about what happened at the teach in with students and Professors. |

SubscribeClick to

AuthorCutcha Risling Baldy is an Associate Professor and Department Chair of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University. She received her PhD in Native American Studies from the University of California, Davis. She is also a writer, mother, volunteer Executive Director for the Native Women's Collective and is currently re-watching My Name is Earl... (5) Top PostsOn telling Native people to just "get over it" or why I teach about the Walking Dead in my Native Studies classes... *Spoiler Alert!*

Hokay -- In which I lead a presentation on what happens when you Google "Native American Women" and critically analyze the images or "Hupas be like dang where'd you get that dentalium cape girl? Showing off all your money! PS: Suck it Victorias Secret"

In which we establish that there was a genocide against Native Americans, yes there was, it was genocide, yes or this is why I teach Native Studies part 3 million

5 Reasons I Wear "Indian" Jewelry or Hupas...we been bling-blingin' since Year 1

Pope Francis decides to make Father Junipero Serra a saint or In Which I Tell Pope Francis he needs to take a Native Studies class like stat

I need to read more Native blogs!A few that I read...

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed