|

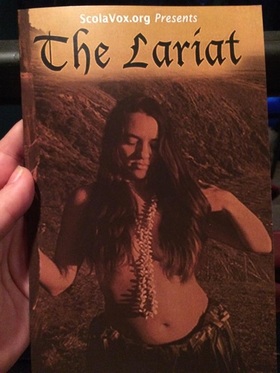

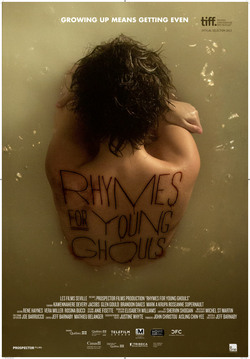

Listen. It would be very easy to think that I spend my time hoping to go to plays (and now operas) that are really problematic and ill-informed representations of Native people so that I can write a blog entry and get everyone on board for how far we still have to go before people actually start being introduced (not interested in, not informed by, not tired of, just INTRODUCED) to narratives that don’t rely on old Hollywood Indian stereotypes that reinforce settler colonialism and excuse genocide. But that’s not true. I actually go hoping to be surprised. This is why it takes me a while to write these things because it takes me a while to process most of the stuff that I see repeated over and over again. My initial reaction to stereotypes and mis-representation of Native people is to explain. I want to explain to people why they wrote the play the way they did and why the story is always about this vanishing, poor, sad, Native who just can’t fight against the oncoming onslaught of progress and civilization. Learning to critically analyze these ever-present justifications of the invasion of the Americas is why everyone should take a Native American studies class because we have to (re)learn what we think we “know.” I had to learn to do it myself, quite honestly. For instance, I have this very clear memory of being a child and telling my mother that Columbus did discover America because he “discovered” it for Europeans. Also, if they wouldn’t have discovered America then we wouldn’t have cars. Yeah, that’s what I said. “Well, without Columbus we wouldn’t have cars. Or cities. Or computers.” And she, in her wisdom, explained (or tried to explain) not that I was wrong, or prejudice, or dumb, but why this this was the story I was taught in schools. “Indian people,” she would say “have to be the sad, less-civilized, other in these stories because then it erases their contributions, it belittles their historical trauma, it renders them useless and primitive so that whatever was happening to them was partially their fault and partially nobody’s fault at all. They become nothing more than a discovery and then a problem. Every policy, every law, every story, every history book has been written to solve what they called the ‘Indian problem.’ And do you know what the ‘Indian problem’ was? That there are Indians.” I find myself saying much the same as I continue to speak up against mis-representation, mis-appropriation, mis-information and mis-guided attempts to portray Indian people in plays, the media, popular culture etc. In many ways, my voice becomes part of their Indian problem. Their problem is that I exist, that I am, that I have a response to their “works of art” and that they feel like I should remain silent because they believe that their earnestness is enough. They don’t mean to erase Native people with their work. They don’t mean to forward ideas about Native people that render them useless and primitive… They don’t mean to be so dismissive of Native people through their storytelling. But they are. Perhaps this is why it has taken me a moment to write a coherent response to a recent opera I went to see in San Francisco, called “The Lariat.” I could take it apart for what it is, or what it isn’t. But I found that I mostly just wanted to tell everyone involved in the production to take a Native American Studies class so they could learn the critical analytical skills necessary to understand why the stereotypes in this opera are so problematic. Which is all a long winded way for me to explain that I went to see the opera “The Lariat” in San Francisco and all I got was this play review in my continuing (unfortunate) series Will this Play be Better Than the Ishi Play? And away we go…  I had way too much fun googling "Indian dudes on romance novels" to find this pic. I had way too much fun googling "Indian dudes on romance novels" to find this pic. After I went to see that one play about Ishi (which was some of the most offensive, traumatic BS I’ve ever had to sit through) I think my tolerance (unfortunately) for bad, stereotypical nonsense has been set somewhat high. My initial response to this new opera, “The Lariat” was “well it’s not minstrel show bad” it’s more like Indian dude on the cover of a dime store romance bad. And, truth be told, it could have been worse. “The Lariat” described as a “dark comic opera” about the Mission Carmel, and the Esselen people is not really about the mission or the Esselen. The mission is the backdrop to a much more convoluted, tragic romance between Padre Luis who loves (unrequited) an Esselen woman (Ishka) but she loves a vaquero (Ruiz Berenda a.k.a Kinikilali) who is half Indian/ half Spanish. It’s based on a novella by a guy named Jaime De Angulo which was written in 1927. The fact that this opera is based on this old novella was a discussion point between me and my friend Angel. My final word on the subject was that the opera should stand on its own. The decisions of the writer, director, producers were made by these individuals in 2015 and stand as an approved portrayal of Native people in 2015. They chose these depictions, not just (or even if they are) because of an old novella.  In the opera, Ishka is billed as a main character. In fact, she is featured on the cover of the playbill, topless, wearing some kind of grass skirt and necklace with the ocean in the background. This is the way she looks when you first see her, or when Father Luis first encounters her on the beach. The scene is supposed to be important, because she’s, I don’t know… boobs. But Ishka is not a main character in this story, neither are any of the Native people. No, this opera is about the missionaries. It’s about one Spanish dude (Father Luis) and the people he covets as “potential converts.” This is not to say that this is the worst thing I have ever seen or that I was ready to walk out of the opera. From a critical feminist standpoint this play is a full on misogynistic patriarchal mess. From a Native studies standpoint this play is not a play for Natives or even about Natives. The Natives are essentially moderately self-sufficient props. Nope, this is a voyeuristic look at Native people through western eyes. From a Cutcha Risling Baldy standpoint all I could really muster after the opera was over was “meh. Good thing I found some m&ms in my jacket pocket.” The Native person who gets the most pointed stage time is Ishka (or the Esselen girl, as she is also billed in the program) and her entire existence revolves around men. She is completely defined by the men in her life, who she in turn inspires to lust, greed, envy, wrath and pride (five of the seven deadly sins ain’t bad). And eventually they all die because they cannot have her, or because they want her too much. Interestingly enough, her songs are all in the Esselen language, so we never really get her perspective, because most of us don’t speak Esselen. When she does speak English, it is about what’s going on in her relationships, or with her men, or in her last song where she is begging for death so she can be with her man. There are many Native women (feminist Native women scholars, Native women leaders) who could have helped to inform a much stronger and more realized character than this Ishka. I kept wanting to apologize to Ishka. “I’m sorry that the playwright/opera writer didn’t want more for you. I’m sorry that you are stuck in a patriarchal, misogynistic trope you can’t get out of.” All the stereotypes are there. (If you want to learn more about Native Women and stereotypes read my blog entry on just that!) Stereotypes including: Native women are like the land so let’s tame and conquer them. After Ishka’s new true love (who is a vaquero) decides to marry her he goes to the woods and sings a song about how much he loves the land, even if it trembles at his touch, even if he can’t have it but just has to look at it and I thought “subtle dude.” Native women are meant to be lusted after, even though they are too “innocent” to know this. Their childlike innocence keeps them from being ashamed of their bodies. Ishka is introduced as a naked woman emerging from the sea, driving men to love her (Venus Demilo) and the thing I immediately write down is “what happened to the rest of her skirt?” For some reason she wore it as a loin cloth, to show all of her legs and barely cover her front and back. She is the natural, the wild, the beauty of the land. She is untamed, wilderness. The padre immediately lusts after her because, well this is never quite clear, but I mostly summarize his love for her as “bewbs.” Native women are tied to nature and spirituality. The defeat of this nature and spirituality will be accomplished through subduing Native women. At one point Ishka (the prop) passively accepts being baptized, which Father Luis pushes her in to doing because otherwise she will be lashed, even though she gets lashed anyway? She doesn’t understand what is going on, but kneels before him and allows him to drip water on her head. Then he starts singing about… wait for it… her bewbs. Native women don’t really like Native dudes. Native dudes kind of bum them out. Ishka and her old Shaman husband lose their baby, somehow? It’s not really clear. She leaves her Shaman husband after their child dies. He longs for her, she never mentions him again. He cries for her in the woods. She shows up to the woods and sings a love song with her new true love, a half Spanish half Indian guy who is the perfect example of assimilation – the padres like him because he is a Catholic, the Indians love him because he is an Indian and he loves her? Because? It’s never really established so maybe…bewbs. When the going gets tough the Native women get going because they long for progress, a “better future” and Native men are old and represent the past. The complete rejection of her Native life is incredibly problematic. I can only infer as an audience member that Ishka blames her Native life for her child’s death. This is a subtle hint that the Native life is bad for you, babies die in this life. She continues to reject her Native life throughout the opera. We hear nothing about her having any other family, as if her marriage to the Shaman is what defined her as a Native person. The other implication is that her marriage to the Shaman was forced, or arranged. And it is only after she goes to the mission that she is able to find “true love.” Again, the implied narrative is that Indian marriages are false, not based on true love, not real. If a Native woman ain’t got no man, then what’s she got to live for? (The future of her people? The rest of her family? To help fight for freedom from the missions? To help keep the other enslaved Esselen safe? To rejoin her community?) Sadly, the only agency Ishka demonstrates is when she decides to kill herself, so she can be with her man. As if she is lost and undefined. As she is singing her song, she begs to be taken to the land of the dead to be with her true love and I thought “which guy will show up?” Will it be her Shaman husband who she never divorced? (She could have divorced him, Native people had divorce). Or will it be her new vaquero (it’s the vaquero)? Other fun tropes that run throughout the opera: Indian people are sad and dying. One of my favorite moments (in song) was when the blue jays showed up to make fun of the crying Shaman and sing “Poor Indians, they are all kind of sad.” Indeed. Indian culture is dying. Indian children are dying. If you are in love with an Indian woman (because…bewbs) then you, much like the culture and children, will soon be dying! The dying Indian story has been told, and told, and told. Why? Because people like their Indians dying. It makes for better “dark comic operas” and also makes for a better excuse. There was tragedy all around. It wasn’t just the tragedy of the missions (which were tragic) but it was the tragedy of the west, it was “manifest destiny” or “manifest tragedy.” I don’t know. When I set out to write this review I thought “what will I say? It wasn’t the most horrible thing I’ve had to sit through.” Granted, there are a lot of problems. The portrayal of women, problem. The stereotypes, problem. The excusing of Mission violence, problem. Still, not the worst. The Ishi play was the worst. That’s what I was going to say. But then I wrote something down at the very end of my notes which I just came across. Set – higher – standards.  Go to Netflix and watch this movie instead of watching the opera. Go to Netflix and watch this movie instead of watching the opera. It was as much advice for myself as anyone else. Dear playwrights, play houses, and audience members: set – higher – standards. Yes, we can tell a better story than this. Yes, we should. Yes, when you take on the responsibility of writing about something or some people who are still struggling to be heard then you have to do more work. People still think the missions were nice places where Natives learned to farm and Padres kissed babies and brought “civilization.” Junipero Serra is being declared a saint! #HesNotASaint Native women suffer from some of the worst rates of violence, most of which are (still) committed by non-Native people. These stories matter and the way we tell them… matters. You should want to do more work. You should want to tell a better story. Ishka deserves better. The Esselen people deserve better. We all deserve better. The opera continues this weekend. You don’t have to go. Instead, head over to Netflix and watch this movie. You’ll thank me for it.

1 Comment

2/4/2015 01:21:38 pm

Hi Cutcha,

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SubscribeClick to

AuthorCutcha Risling Baldy is an Associate Professor and Department Chair of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University. She received her PhD in Native American Studies from the University of California, Davis. She is also a writer, mother, volunteer Executive Director for the Native Women's Collective and is currently re-watching My Name is Earl... (5) Top PostsOn telling Native people to just "get over it" or why I teach about the Walking Dead in my Native Studies classes... *Spoiler Alert!*

Hokay -- In which I lead a presentation on what happens when you Google "Native American Women" and critically analyze the images or "Hupas be like dang where'd you get that dentalium cape girl? Showing off all your money! PS: Suck it Victorias Secret"

In which we establish that there was a genocide against Native Americans, yes there was, it was genocide, yes or this is why I teach Native Studies part 3 million

5 Reasons I Wear "Indian" Jewelry or Hupas...we been bling-blingin' since Year 1

Pope Francis decides to make Father Junipero Serra a saint or In Which I Tell Pope Francis he needs to take a Native Studies class like stat

I need to read more Native blogs!A few that I read...

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed