|

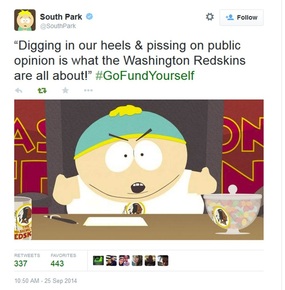

I got a really great message from a college student just the other day. She was very gracious and asked me if I could offer her some feedback on certain issues that she has faced navigating her way through college as a Native American student. Because I’m deep into writing my dissertation, my blogging is few and far between as I try to finish something that resembles coherent thought in an academic way. (If only I could write a series of blogs and call it a dissertation! Someday!) It is because of her letter that I am starting a three part series inspired by some things that she asked me in the hopes of providing her (and other Native peoples) with a response to what (IMHO) are some pretty salient and important issues that come up CONSTANTLY and just go to show that everyone, who has ever existed, anywhere, should take a Native American Studies class. This entry is about the “99 questions.” That’s how she referred to it. “…what advice would you give Native college students who endure the dreaded 99 questions of what it’s like being Indian (you know the stereotypical: “Do you live in a teepee? Can I touch our hair? Do you get free stuff? Why are you guys so lazy?” etc. etc.)” As I was nodding away it got me to thinking, what are those 99 questions? How have they (or haven’t they) changed since, oh I don’t know, 1492, when this one guy jumped off a boat and went “So, this is India. Can I touch your hair?” (And take you prisoner and make you slaves and generally bring about massive destruction and genocide upon your people. #SuckItColumbus) Because I am someone who is constantly reading all the heavy duty stuff that comes out of academics trying to put in to words the feelings we all have and make it theory (so for instance instead of saying “that dude is a butt head” they have to write “that individual person is affected by patriarchal standards of masculinity.”) my immediate instinct when someone asks me one of the “99 questions” is to over analyze why that is the question they are asking. What is the historical context for that question? What makes them think that is the proper question to ask? Where does that question come from? Why do the questions focus on certain stereotypes of Native people but don’t focus on modern issues of self-determination or sovereignty? What’s so great about my hair? (Answer: I bought this new kind of expensive celebrity endorsed conditioner which I have to hoard because both my husband and daughter are constantly trying to use it.) In this first attempt at a real response to this young woman I offer the following lists in a blog entry I am calling: I Got 99 Questions and “How can I honor the treaties and support self-determination for Native peoples” ain’t one. Five "usual suspects" questions that I have been asked Do you live in a tee pee? No. One of my white hippie friends lived in a teepee when he was a kid. I did not. Do you have an Indian name? It’s Cutcha. No seriously. It means Blue Jay. I think I’m part Indian too. Is there a test for that? Where can I get that test? I should make that test and give it out to people. “Are you a real Indian Quiz.” It will be a multiple choice test. There will be no right answers. (Ba Dum Dum… wait… that’s kind of deep…) I’m Native too. What am I entitled too? (Alternative question: you are Native? Don’t you get a lot of stuff from the Government?) *Actual Answer that I just gave to someone the other day because I was asked this question* You know a year ago the Supreme Court allowed for the legal kidnapping of a Native girl from her loving father. He is Cherokee, and she is Cherokee but she was adopted by a non-Native family who felt entitled to her. They sued to keep her after she was taken away from them so she could live with her father who had been fighting for her for years. It was because of the Indian Child Welfare Act that he was able to gain custody. You see, they had adopted her illegally and without following this federal law that protects Indian children by setting up a system that encourages these children to be cared for by an Indian parent, relative or tribal member. Why? Because for a number of years the foster system and adoption system was biased against Indian families. In fact you had instances in which there were more Indian children in foster care than other groups, even though Native people are often less than 1% of the population. This bias was engrained. It was a part of a system that was designed to break apart Indian families. It comes from a long historical record of trying to solve the “Indian problem” by assimilating children so they will be less “Native.” This causes years upon years of trauma. There are still tribal peoples who reel from the impacts of being taken from their families. There are communities, who are still re-learning what it means to feel safe enough that they can parent and not fear losing their children to a system set up against them. In the end, even though the law supported him being a father to his daughter, and the tribe supported him and basic human decency supported him, his daughter was seized from him by government agents because the Supreme Court had decided that this non-Native couple deserved this child. And it was heartbreaking. And to this day when I talk about this case, I have to pause… sometimes for a few long moments… to breathe… because the night they seized her even though I was miles and miles away from Oklahoma I felt it. I stood in the doorway of my daughter’s room and I watched her sleep and I thought “I would never let her go.” All that is to say, as a Native, the things we “get” from the government, the things we are “entitled to” include getting our children taken away from us. How come you can’t just get over it? I answered this one before (check it out!). But I have to include it because… it happens. Also alternative question: The (insert other racial group here) people suffered too. They suffered more than Natives. How come they got over it? And you can’t? This question came up a lot after I wrote the blog about the Walking Dead and why Natives can’t just “get over it.” And I started doing an exploration of this idea that Tony Platt called “competitive suffering.” He said something to me like “as if we want to enter in to competitive suffering.” And immediately I pictured an Olympic Games type situation with a “competitive suffering” tournament. You know who wins that tournament – Danny Snyder probably. He’s so good at suffering. (In South Park. The South Park version of him is a great competitive suffer-er.) My answer to this question about “how come everybody else gets over it and you haven’t” is “read… more.” Your erasure of the ways that many of these peoples are still engaging with their own historical trauma is everywhere. The fact that you are erasing it because you want to see the world as devoid of the trauma of genocide, slavery, removal (of not just Indian people, but several groups who were removed in various situations) and confinement does not mean that it doesn’t exist. Also – why do you think you are over it? Because you don’t know about it? Because you think it doesn’t affect who you are today? You’re not “over it.” (Freud would say you’re in denial. Jung would say “Shut up Freud, you don’t know nothing about nothing.” Freud would jump up and say “stop being jealous of me! And your mom! You just love your mom!” Man, you can’t get nothing done once Freud starts talking about your mom.) Also, what I’ve said before. “Actually, I am over it” which is why… it’s time to really talk about it. P.S. These “usual suspects” questions come from very particular places but mostly they are about the continued erasure of Indian people from a modern discussion of the Indian experience. It is a testament and clear example of how much people don’t learn about the place they live (as in the United States, or Canada, or Mexico, or South America or any country really). Three questions I have been asked in the past two weeks  Did you see the ("disgraced, soon-to-be former") Navajo President sitting in the box with the owner of the Washington (RACIAL SLUR *BEEEEP*) team? Yes. Follow up question: What did you think? Well. I thought it looked desperate and transparent. Does anybody really think that having a Native person sitting with you means that somehow using a racial slur as a team name is okay and we should all just go home? No. Because I have a lot of non-Native Football fans who are my friends. Sometimes they sit next to me too (granted not in a stadium box, but on my futon). They think the team name is racist and being complacent to that racism because “it doesn’t affect me” or because you want to sell stuff at football stadiums is just contributing to a continued degradation of all of our society. WE ALL DESERVE BETTER than having a racial slur as a team name. Which is my way of saying that for every person you get to sit in your box with your merchandise I can find another person who KNOWS that the name has got to go. Getting Indians on your side is not the issue any way. The team name is a *racial slur* -- There is #NoJustification for it. I know you say a lot of stuff about appropriation and stuff. Is this shirt okay? (Is this bag okay? Are these earrings okay? I have a dream catcher in my room, is that okay?) I wrote a blog about this too before, if you want to read it. What did you think about that episode of South Park? (What did you think about the Daily Show? What did you think about this one episode of the Family Guy I saw once? What do you think about John Redcorn?) Short answers: Liked it. Liked it. Depends on the episode. He’s cool. Longer answer: Representation of Native People on TV is… still lacking in my opinion. I call it the “Native Cameo.” We don’t (yet) have a series that features a Native character as a major player. Native characters (mostly) get treated as cameos. Quick mentions, then they go away and we get back to our regular programming. I see what it means for people to be exposed to Native people in this way, whether it be young Native children who really do acknowledge and hold on to each and every portrayal, or non-Native people who might not ever have an experience of understanding that there are “modern” Native American people. Our TV watching experiences do shape us, even though they probably shouldn’t. We laugh at certain things, which tells us about who we are, we learn from certain things, which tells us about who we are, we hold on to certain ideas… which informs for us how the world should function. So the Native cameo… matters. How we see each other becomes important to how we treat each other. When Native peoples are invisible, we are often treated as invisible. We are not invited to participate in government discussions, we are treated as less than “stakeholders,” we are told that the destruction of our sacred spaces is of little consequence to anything, we become invisible to the public who says “but wait, no Native Americans really care about this issue because…” So when people see us on TV and they hear what we have to say… it matters. Actual Questions I was asked by a group of 6 year olds at a presentation:

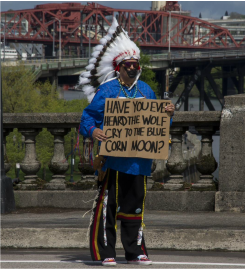

I love going to present to kids mostly because they are pretty much the most attentive and awed audience you’re ever going to get. Everything I say they go “wow! Ooo! Awesome!” and the moment that I bring out some baskets that they can touch and hold their eyes light up. I have let some of them try on my hat, and they are the most respectful group of people. They ask millions of questions about the proper way to wear something. They are very gentle. And they look for clues from me as to what is okay or not okay, never assuming that they know better. I include their questions because they illustrate to me what happens when you are able to interact with Native people from a young age, where Native people become real and not exotic museum relics. To them I am “so and so’s Mom” or “so and so’s Auntie” or “so and so’s friend.” They start to see Native people as being real (which is a first step) and then as being authorities on who they are. Instead of thinking “you aren’t like what the books say or what the movies say” they take you at your word. So Native experiences and ideas and people can be varied, they are people first and foremost. The curiosity of children that I have presented to is never about “how do I challenge your authenticity while also making you and exotic specimen while also dehumanizing you while also re-establishing my beliefs about who you should be.” Instead, they want to learn. This might be part of the problem with the 99 questions. I like to think that most people are asking these questions because they are genuinely trying to learn something about Native people that they don’t get in their classrooms, on their TVs, in their books, or on the You Tubes. They also don’t know how to access this information because it is not made readily available to them (not yet, there are many of us working on that). Native American Studies is not (yet) a requirement course for all people, but they want to know. They genuinely are still like those six year olds with rapt attentions. The problem is this can get tiring and exhausting and sometimes you just want to be an Indian at Whole Foods, or sometimes you just want to be an Indian in economics class who talks about the economics of development on Native reservations (pitfalls and benefits) but who doesn’t want to have explain that this does not in anyway involve hearing the wolf cry to the blue corn moon (or painting with all the colors of the wind). My advice then becomes this. Answer as many questions to as many people as you can stand. And when you can’t stand it anymore, smile, take a deep breath and say “My Ask a Native office hours are over for today. You should really take a Native American Studies class.” Addendum Question: Can I touch your hair? (Can I touch your hat? Can I touch your "costume?" Can I touch your necklace?)

No.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SubscribeClick to

AuthorCutcha Risling Baldy is an Associate Professor and Department Chair of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University. She received her PhD in Native American Studies from the University of California, Davis. She is also a writer, mother, volunteer Executive Director for the Native Women's Collective and is currently re-watching My Name is Earl... (5) Top PostsOn telling Native people to just "get over it" or why I teach about the Walking Dead in my Native Studies classes... *Spoiler Alert!*

Hokay -- In which I lead a presentation on what happens when you Google "Native American Women" and critically analyze the images or "Hupas be like dang where'd you get that dentalium cape girl? Showing off all your money! PS: Suck it Victorias Secret"

In which we establish that there was a genocide against Native Americans, yes there was, it was genocide, yes or this is why I teach Native Studies part 3 million

5 Reasons I Wear "Indian" Jewelry or Hupas...we been bling-blingin' since Year 1

Pope Francis decides to make Father Junipero Serra a saint or In Which I Tell Pope Francis he needs to take a Native Studies class like stat

I need to read more Native blogs!A few that I read...

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed